Genome sequencing has made remarkable strides since the initiation of “The Human Genome Project” in 1990. Still, there are many challenges that must be overcome before this methodology can reach its fullest potential and be useful in serving as a method of Cannabis sativa genetics verification and tracking throughout the cannabis supply chain. Several major milestones that must be realized include end-to-end haploid type (single, unpaired set of chromosomes instead of complete paired set or “diploid”), long read, resolved genome sequences at a reasonable cost within a reasonable timeframe and with confidence in accuracy (Mostovoy et al.). These genomes are typically generated as shorter reads that are then scaffolded (Fig 1.) or matched to reference genomes in order to build a longer continuous read. While shorter sequencing reads indeed lower the cost barrier for producing more genomic data, it has created another issue as a result of this short-read technology.

There are two main issues with the more affordable short read sequencing methodology, the first being that sequential variants are typically not detected, especially if they involve a ton of repeats/inverted repeats, due to the limitation of the current referenced Cannabis genomes and the mapping process of the short-read sequences. This is especially unfortunate because larger variants can have up to a 13% variance within a diploid multichromosomal genome, such as Cannabis sativa, and this variance is thought to largely contribute to disease in various species, or maybe terpene profile in Cannabis sativa. Not being able to detect these variances with more affordable sequencing methodologies is particularly problematic and reference genomes produced with short read sequences are typically highly fragmented. The second limitation is the inherent errors, gaps and other ambiguities associated with taking tons of short read sequences and combining them all, like a jigsaw puzzle, in order to draft the larger genomic picture. While there is software with algorithms to assist in deciphering raw sequences, there is still much more work to be done on this challenge, considering that cannabis genome sequencing is new genomics territory. Unfortunately, as researchers seek higher and higher levels of data quality, shortcomings of this type of sequencing technology begin to become apparent. This sort of sequencing methodology relies heavily on reference sequences. This isn’t much of an issue with microbial genomes, which tend to be rather short and typically have one chromosome, however, when seeking to analyze much longer genomes with multiple diploid chromosomes and tons of mono and dinucleotide repeats, problems arise (English et al.).

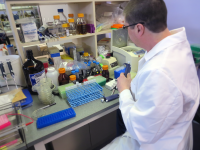

The other category of sequencing is long read sequencing. Long read sequencing is as it sounds, the deciphering of much longer DNA strands. Of course, the technology is limited by the quality of the DNA captured, therefore, special high molecular weight DNA extraction protocols must be deployed in order to obtain the proper DNA quality (Fig. 3). Once this initial limitation is overcome there is the stark cost of long read sequencing technology. PacBio without a doubt makes one of the highest quality long read sequence generating instruments that has ever graced the field of biotechnology, but due to the steep price tag of the machine, progress in this field has been stifled simply because it just isn’t affordable and the read depth for mammalian and plant genomes is currently almost completely prohibitive until read lengths double in length for this instrumentation. In order to produce what is considered to be a “validated genome” both short read and long read sequencing methodologies are combined. Long read sequencing data is used to produce the reference contigs because they are much easier to assemble, then short read sequencing is scaffolded against the reference contigs as a sort of “consensus validation” of the long read contigs.

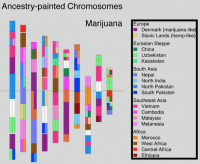

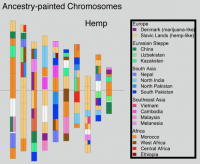

Despite the shortcoming of utilizing short read sequencing technology for analysis of the cannabis genome, it is still useful especially when combined with other longer read sequencing technologies or optical mapping technologies. Kevin McKernan, chief scientific officer of Medicinal Genomics, has been working feverishly to bridge the information gap between the cannabis genome and other widely studied plant genomes. As a scientist that worked on the Human Genome Project in 2001, McKernan has a demonstrated history of brilliance in the field of genomics. This paved the way for him to coordinate the first crypto funded and blockchain notarized sequencing project (DASH DAO funded) (Fig. 2), which was completed in 60 days, and surprisingly showed that the cannabis genome is over 1 billion bases long which is 30% larger than any cannabis genome submitted prior to his work. By reaching the standard of 500kb N50 set forth by the Human Genome Project, Kevin McKernan was able to see new aspects of the cannabis genome that were not visible due to the fragmented genomic data previously generated. Information such as a possible linkage of THCA synthase and CBDA synthase genes is crucial when seeking to use the cannabis genome for verification and tracking purposes. This is because special linkages can be considered a type of “genetic marker” that may be used to differentiate cannabis cultivars and lineages. There are many types of genetic markers, including SNP (single nucleotide polymorphisms), VNTR (variable number tandem repeats) and even patterns of gene expression. Funding and recording of cannabis genomics must be further developed in order for potential markers to be identified and validated via larger scale genome-wide association studies.

These technologies, when combined, often reduce the number of scaffolds while increasing the percent of resolved genome by filling in gaps within the drafted genome. Nanopore sequencing is an especially interesting and innovative sequencing technology that is useful in many ways. One of the most powerful uses of this technology is its ability to upgrade the quality of draft and pushed genomes by resolving poorly organized genomes and genomic structure for a fraction of the time and cost of other long read sequencing platforms (Jian et al.), making it an excellent candidate for solving cost and time constraints. Nanopore’s portability and convenience makes it a real-time solution to solving genetics-based problems and questions. A notable use of this technology is recorded during an epidemiological outbreak in Africa, its proof of concept in pathogen detection in space, and its ability to detect base modifications during sequencing process. Even still there are more uses to this exciting technology and it has the potential to elevate cannabis genomics and the field of genomics entirely, while remaining portable and expeditious. A shortcoming of the Nanopore sequencing platform is its low sequencing coverage, which makes this platform inefficient for applications like haplotype phasing and single nucleotide variant detection due to the number of variants to be detected being smaller than the published variant-detection error rates of algorithms using MinION data. Single nucleotide variants can be considered to be genetic markers, especially markers for disease, so this is what inhibits Nanopore from resolving our cannabis genome sequencing problems, as of today.

There are genetic markers to discover, molecular biology protocols to optimize, and industry wide potential for exciting collaborationMany algorithmic problems seem to occur due to input data quality. Typical input data quality suffers as the reads get longer and the sequencing depth gets shorter, resulting in not enough data being generated by the sequencing to provide confidence in the genome assembly. To mitigate this, scientists may decide to fractionate a genome, sequence it, or they may clone a difficult to sequence region with highly repetitive regions in order to produce reads with greater depth and thus resolve the region. They can then perform single molecule sequencing to resolve genome structure then determine and confirm the place of the cloned region. Thus, it seems that the best solution to the limitation of algorithms is to be aware of sequencing platform limitations and compensate for these limitations by using more than one sequencing platform to obtain enough pertinent data to confidently produce authentic, “validated” genome assemblies (Huddleston et al.). With input data being critical in producing accurate sequencing data, standardization of DNA isolation protocols, extraction reagents and any enzymes utilized may be deemed necessary.

To conclude, the field of cannabis genomics is teeming with opportunities. There are genetic markers to discover, molecular biology protocols to optimize, and industry wide potential for exciting collaboration. More states will need to take into account the lack of federal government research grant availability and begin to think of creative ways to get cannabis science funds to continue the development of this industry. Specifically speaking, developing a feasible method for genetic tracking of cannabis plants will require improvements within the availability of sequencing technology, improvements in deploying the resources to these projects in order for them to be completed expeditiously, and standardization/validation of methods and SOPs used in order to increase confidence in the accuracy of the data generated.

A special thank you to all of my cannabis industry mentors that have molded and elevated my understanding of current needs and applied technologies within the cannabis industry, without you there would be no career within this industry for me. You are immensely appreciated.

Citations

Bickhart, D. M., Rosen, B. D., Koren, S., Sayre, B. L., Hastie, A. R., Chan, S., . . . Smith, T. P. (2017). Single-molecule sequencing and chromatin conformation capture enable de novo reference assembly of the domestic goat genome. Nature Genetics,49(4), 643-650. doi:10.1038/ng.3802

English, A. C., Salerno, W. J., Hampton, O. A., Gonzaga-Jauregui, C., Ambreth, S., Ritter, D. I., . . . Gibbs, R. A. (2015). Assessing structural variation in a personal genome—towards a human reference diploid genome. BMC Genomics,16(1). doi:10.1186/s12864-015-1479-3

Huddleston, J., Ranade, S., Malig, M., Antonacci, F., Chaisson, M., Hon, L., . . . Eichler, E. E. (2014). Reconstructing complex regions of genomes using long-read sequencing technology. Genome Research,24(4), 688-696. doi:10.1101/gr.168450.113

Jain, M., Olsen, H. E., Paten, B., & Akeson, M. (2016). The Oxford Nanopore MinION: Delivery of nanopore sequencing to the genomics community. Genome Biology,17(1). doi:10.1186/s13059-016-1103-0

Mostovoy, Y., Levy-Sakin, M., Lam, J., Lam, E. T., Hastie, A. R., Marks, P., . . . Kwok, P. (2016). A hybrid approach for de novo human genome sequence assembly and phasing. Nature Methods,13(7), 587-590. doi:10.1038/nmeth.3865