Facility layout and design are important components of overall operations, both in terms of maximizing the effectiveness and efficiency of the process(es) executed in a facility, and in meeting the needs of personnel. Prior to the purchase of an existing building or investing in new construction, the activities and processes that will be conducted in a facility must be mapped out and evaluated to determine the appropriate infrastructure and flow of processes and materials. In cannabis markets where vertical integration is the required business model, multiple product and process flows must be incorporated into the design and construction. Materials of construction and critical utilities are essential considerations if there is the desire to meet Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) compliance or to process in an ISO certified cleanroom. Regardless of what type of facility is needed or desired, applicable local, federal and international regulations and standards must be reviewed to ensure proper design, construction and operation, as well as to guarantee safety of employees.

Materials of Construction

The materials of construction for interior work surfaces, walls, floors and ceilings should be fabricated of non-porous, smooth and corrosive resistant surfaces that are easily cleanable to prevent harboring of microorganisms and damage from chemical residues. Flooring should also provide wear resistance, stain and chemical resistance for high traffic applications. ISO 22196:2011, Measurement Of Antibacterial Activity On Plastics And Other Non-Porous Surfaces22 provides a method for evaluating the antibacterial activity of antibacterial-treated plastics, and other non-porous, surfaces of products (including intermediate products). Interior and exterior (including the roof) materials of construction should meet the requirements of ASTM E108 -11, Standard Test Methods for Fire Tests of Roof Covering7, UL 790, Standard for Standard Test Methods for Fire Tests of Roof Coverings 8, the International Building Code (IBC) 9, the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 11, Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and other applicable building and safety standards, particularly when the use, storage, filling, and handling of hazardous materials occurs in the facility.

Utilities

Critical and non-critical utilities need to be considered in the initial planning phase of a facility build out. Critical utilities are the utilities that when used have the potential to impact product quality. These utilities include water systems, heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC), compressed air and pure steam. Non-critical utilities may not present a direct risk to product quality, but are necessary to support the successful, compliant and safe operations of a facility. These utilities include electrical infrastructure, lighting, fire detection and suppression systems, gas detection and sewage.

- Water

Water quality, both chemical and microbial, is a fundamental and often overlooked critical parameter in the design phase of cannabis operations. Water is used to irrigate plants, for personnel handwashing, potentially as a component in compounding/formulation of finished goods and for cleaning activities. The United States Pharmacopeia (USP) Chapter 1231, Water for Pharmaceutical Purposes 2, provides extensive guidance on the design, operation, and monitoring of water systems. Water quality should be tested and monitored to ensure compliance to microbiological and chemical specifications based on the chosen water type, the intended use of the water, and the environment in which the water is used. Microbial monitoring methods are described in USP Chapter 61, Testing: Microbial Enumeration Tests 3and Chapter 62, Testing: Tests for Specified Microorganisms 4, and chemical monitoring methods are described in USP Chapter 643, Total Organic Carbon 5, and Chapter 645, Water Conductivity 6.Overall water usage must be considered during the facility design phase. In addition to utilizing water for irrigation, cleaning, product processing, and personal hygiene, water is used for heating and cooling of the HVAC system, fogging in pest control procedures and in wastewater treatment procedures A facility’s water system must be capable of managing the amount of water required for the entire operation. Water usage and drainage must meet environmental protection standards. State and local municipalities may have water usage limits, capture and reuse requirements and regulations regarding runoff and erosion control that must also be considered as part of the water system design.

- Lighting

Lighting considerations for a cultivation facility are a balance between energy efficiency and what is optimal for plant growth. The preferred lighting choice has typically been High Intensity Discharge (HID) lighting, which includes metal halide (MH) and high-pressure sodium (HPS) bulbs. However, as of late, light-emitting diodes (LED) systems are gaining popularity due to increased energy saving possibilities and innovative technologies. Adequate lighting is critical for ensuring employees can effectively and safely perform their job functions. Many tasks performed on the production floor or in the laboratory require great attention to detail. Therefore, proper lighting is a significant consideration when designing a facility.

- HVAC

Environmental factors, such as temperature, relative humidity (RH), airflow and air quality play a significant role in maintaining and controlling cannabis operations. A facility’s HVAC system has a direct impact on cultivation and manufacturing environments, and HVAC performance may make or break the success of an operation. Sensible heat ratios (SHRs) may be impacted by lighting usage and RH levels may be impacted by the water usage/irrigation schedule in a cultivation facility. Dehumidification considerations as described in the National Cannabis Industry Association (NCIA) Committee Blog: An Introduction to HVACD for Indoor Plant Environments – Why We Should Include a “D” for Dehumidification 26 are critical to support plant growth and vitality, minimize microbial proliferation in the work environment and to sustain product shelf-life/stability. All of these factors must be evaluated when commissioning an HVAC system. HVAC systems with monitoring sensors (temperature, RH and pressure) should be considered. Proper placement of sensors allows for real-time monitoring and a proactive approach to addressing excursions that could negatively impact the work environment.

- Compressed Air

Compressed air is another, often overlooked, critical component in cannabis operations. Compressed air may be used for a number of applications, including blowing off and drying work surfaces and bottles/containers prior to filling operations, and providing air for pneumatically controlled valves and cylinders. Common contaminants in compressed air are nonviable particles, water, oil, and viable microorganisms. Contaminants should be controlled with the use appropriate in-line filtration. Compressed air application that could impact final product quality and safety requires routine monitoring and testing. ISO 8573:2010, Compressed Air Specifications 21, separates air quality levels into classes to help differentiate air requirements based on facility type.

- Electrical Infrastructure

Facilities should be designed to meet the electrical demands of equipment operation, lighting, and accurate functionality of HVAC systems. Processes and procedures should be designed according to the requirements outlined in the National Electrical Code (NEC) 12, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) 13, National Electrical Safety Code (NESC) 14, International Building Code (IBC) 9, International Energy Conservation Code (IECC) 15 and any other relevant standards dictated by the Authority Having Jurisdiction (AHJ).

- Fire Detection and Suppression

“Facilities should be designed so that they can be easily expanded or adjusted to meet changing production and market needs.”Proper fire detection and suppression systems should be installed and maintained per the guidelines of the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 11, International Building Code (IBC) 9, International Fire Code (IFC) 10, and any other relevant standards dictated by the Authority Having Jurisdiction (AHJ). Facilities should provide standard symbols to communicate fire safety, emergency and associated hazards information as defined in NFPA 170, Standard for Fire Safety and Emergency Symbols 27.

- Gas detection

Processes that utilize flammable gasses and solvents should have a continuous gas detection system as required per the IBC, Chapter 39, Section 3905 9. The gas detection should not be greater than 25 percent of the lower explosive limit/lower flammability limit (LEL/LFL) of the materials. Gas detection systems should be listed and labeled in accordance with UL 864, Standard for Control Units and Accessories for Fire Alarm Systems 16 and/or UL 2017, Standard for General-Purpose Signaling Devices and Systems 17 and UL 2075, Standard for Gas and Vapor Detectors and Sensors 18.

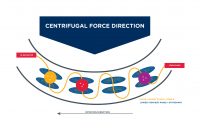

Product and Process Flow

Product and process flow considerations include flow of materials as well as personnel. The classic product and process flow of a facility is unidirectional where raw materials enter on one end and finished goods exit at the other. This design minimizes the risk of commingling unapproved and approved raw materials, components and finished goods. Facility space utilization is optimized by providing a more streamlined, efficient and effective process from batch production to final product release with minimal risk of errors. Additionally, efficient flow reduces safety risks to employees and an overall financial risk to the organization as a result of costly injuries. A continuous flow of raw materials and components ensures that supplies are available when needed and they are assessable with no obstructions that could present a potential safety hazard to employees. Proper training and education of personnel on general safety principles, defined work practices, equipment and controls can help reduce workplace accidents involving the moving, handling, and storing of materials.

Facilities Management

Facilities management includes the processes and procedures required for the overall maintenance and security of a cannabis operation. Facilities management considerations during the design phase include pest control, preventative maintenance of critical utilities, and security.

A Pest Control Program (PCP) ensures that pest and vermin control is carried out to eliminate health risks from pests and vermin, and to maintain the standards of hygiene necessary for the operation. Shipping and receiving areas are common entryways for pests. The type of dock and dock lever used could be a welcome mat or a blockade for rodents, birds, insects, and other vermin. Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) should define the procedure and responsibility for PCP planning, implementation and monitoring.

Routine preventative maintenance (PM) on critical utilities should be conducted to maintain optimal performance and prevent microbial and/or particulate ingress into the work environment. Scheduled PMs may include filter replacement, leak and velocity testing, cleaning and sanitization, adjustment of airflow, the inspection of the air intake, fans, bearings and belts and the calibration of monitoring sensors.

In most medical cannabis markets, an established Security Program is a requirement as part of the licensing process. ASTM International standards: D8205 Guide for Video Surveillance System 23, D8217 Guide for Access Control System[24], and D8218 Guide for Intrusion Detection System (IDS) 25 provide guidance on how to set up a suitable facility security system and program. Facilities should be equipped with security cameras. The number and location of the security cameras should be based on the size, design and layout of the facility. Additional cameras may be required for larger facilities to ensure all “blind spots” are addressed. The facility security system should be monitored by an alarm system with 24/7 tracking. Retention of surveillance data should be defined in an SOP per the AHJ. Motion detectors, if utilized, should be linked to the alarm system, automatic lighting, and automatic notification reporting. The roof area should be monitored by motion sensors to prevent cut-and-drop intrusion. Daily and annual checks should be conducted on the alarm system to ensure proper operation. Physical barriers such as fencing, locked gates, secure doors, window protection, automatic access systems should be used to prevent unauthorized access to the facility. Security barriers must comply with local security, fire safety and zoning regulations. High security locks should be installed on all doors and gates. Facility access should be controlled via Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) access cards, biometric entry systems, keys, locks or codes. All areas where cannabis raw material or cannabis-derived products are processed or stored should be controlled, locked and access restricted to authorized personnel. These areas should be properly designated “Restricted Area – Authorized Personnel Only”.

Future Expansion

The thought of expansion in the beginning stages of facility design is probably the last thing on the mind of the business owner(s) as they are trying to get the operation up and running, but it is likely the first thing on the mind of investors, if they happen to be involved in the business venture. Facilities should be designed so that they can be easily expanded or adjusted to meet changing production and market needs. Thought must be given to how critical systems and product and process flows may be impacted if future expansion is anticipated. The goal should be to minimize down time while maximizing space and production output. Therefore, proper up-front planning regarding future growth is imperative for the operation to be successful and maintain productivity while navigating through those changes.

References:

- United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA).

- United States Pharmacopeia (USP) Chapter <1231>, Water for Pharmaceutical Purposes.

- United States Pharmacopeia (USP) Chapter <61>, Testing: Microbial Enumeration Tests.

- United States Pharmacopeia (USP) Chapter <62>, Testing: Tests for Specified Microorganisms.

- United States Pharmacopeia (USP) Chapter <643>, Total Organic Carbon.

- United States Pharmacopeia (USP) Chapter <645>, Water Conductivity.

- ASTM E108 -11, Standard Test Methods for Fire Tests of Roof Coverings.

- UL 790, Standard for Standard Test Methods for Fire Tests of Roof Coverings.

- International Building Code (IBC).

- International Fire Code (IFC).

- National Fire Protection Association (NFPA).

- National Electrical Code (NEC).

- Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE).

- National Electrical Safety Code (NESC).

- International Energy Conservation Code (IECC).

- UL 864, Standard for Control Units and Accessories for Fire Alarm Systems.

- UL 2017, Standard for General-Purpose Signaling Devices and Systems.

- UL 2075, Standard for Gas and Vapor Detectors and Sensors.

- International Society for Pharmaceutical Engineers (ISPE) Good Practice Guide.

- International Society for Pharmaceutical Engineers (ISPE) Guide Water and Steam Systems.

- ISO 8573:2010, Compressed Air Specifications.

- ISO 22196:2011, Measurement Of Antibacterial Activity On Plastics And Other Non-Porous Surfaces.

- D8205 Guide for Video Surveillance System.

- D8217 Guide for Access Control Syst

- D8218 Guide for Intrusion Detection System (IDS).

- National Cannabis Industry Association (NCIA): Committee Blog: An Introduction to HVACD for Indoor Plant Environments – Why We Should Include a “D” for Dehumidification.

- NFPA 170, Standard for Fire Safety and Emergency Symbols.