Across the country, there is a patchwork of regulatory requirements that vary from state to state. Regulations focus on limiting microbial impurities (such as mold) present in cannabis in order for consumers to receive a safe product. When cultivators in Colorado and Nevada submit their cannabis product to laboratories for testing, they are striving to meet total yeast and mold count (TYMC) requirements.In a nascent industry, it is prudent for state regulators to reference specific testing methodologies so that an industry standard can be established.

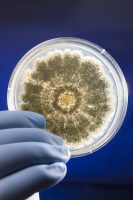

TYMC refers to the number of colony forming units present per gram (CFU/g) of cannabis material tested. CFU is a method of quantifying and reporting the amount of live yeast or mold present in the cannabis material being tested. This number is determined by plating the sample, which involves spreading the sample evenly in a container like a petri dish, followed by an incubation period, which provides the ideal conditions for yeast and mold to grow and multiply. If the yeast and mold cells are efficiently distributed on a plate, it is assumed that each live cell will give rise to a single colony. Each colony produces a visible spot on the plate and this represents a single CFU. Counting the numbers of CFU gives an accurate estimate on the number of viable cells in the sample.

The plate count methodology for TYMC is standardized and widely accepted in a variety of industries including the food, cosmetic and pharmaceutical industries. The FDA has published guidelines that specify limits on total yeast and mold counts ranging from 10 to 100,000 CFU/g. In cannabis testing, a TYMC count of 10,000 is commonly used. TYMC is also approved by the AOAC for testing a variety of products, such as food and cosmetics, for yeast and mold. It is a fairly easy technique to perform requiring minimal training, and the overall cost tends to be relatively low. It can be utilized to differentiate between dead and live cells, since only viable living cells produce colonies.

Photo courtesy of USDA ARS & Peggy Greb.

There is a 24 to 48-hour incubation period associated with TYMC and this impedes speed of testing. Depending on the microbial levels in a sample, additional dilution of a cannabis sample being tested may be required in order to count the cells accurately. TYMC is not species-specific, allowing this method to cover a broad range of yeast and molds, including those that are not considered harmful. Studies conducted on cannabis products have identified several harmful species of yeast and mold, including Cryptococcus, Mucor, Aspergillus, Penicillium and Botrytis Cinerea. Non-pathogenic molds have also been shown to be a source of allergic hypersensitivity reactions. The ability of TYMC to detect only viable living cells from such a broad range of yeast and mold species may be considered an advantage in the newly emerging cannabis industry.

After California voted to legalize recreational marijuana, state regulatory agencies began exploring different cannabis testing methods to implement in order to ensure clean cannabis for the large influx of consumers.

Unlike Colorado, California is considering a different route and the recently released emergency regulations require testing for specific species of Aspergillus mold (A. fumigatus, A. flavus, A. niger and A. terreus). While Aspergillus can also be cultured and plated, it is difficult to differentiate morphological characteristics of each species on a plate and the risk of misidentification is high. Therefore, positive identification would require the use of DNA-based methods such as polymerase chain reaction testing, also known as PCR. PCR is a molecular biology technique that can detect species-specific strains of mold that are considered harmful through the amplification and analysis of DNA sequences present in cannabis. The standard PCR testing method can be divided into four steps:

- The double stranded DNA in the cannabis sample is denatured by heat. This refers to splitting the double strand into single strands.

- Primers, which are short single-stranded DNA sequences, are added to align with the corresponding section of the DNA. These primers can be directly or indirectly labeled with fluorescence.

- DNA polymerase is introduced to extend the sequence, which results in two copies of the original double stranded DNA. DNA polymerases are enzymes that create DNA molecules by assembling nucleotides, the building blocks of DNA.

- Once the double stranded DNA is created, the intensity of the resulting fluorescence signal can uncover the presence of specific species of harmful Aspergillus mold, such as fumigatus.

These steps can be repeated several times to amplify a very small amount of DNA in a sample. The primers will only bind to the corresponding sequence of DNA that matches that primer and this allows PCR to be very specific.

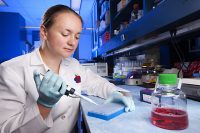

Photo courtesy of USDA ARS & Peggy Greb.

PCR is a very sensitive and selective method with many applications. However, the instrumentation utilized can be very expensive, which would increase the overall cost of a compliance test. The high sensitivity of the method for the target DNA means that there are possibilities for a false positive. This has implications in the cannabis industry where samples that test positive for yeast and mold may need to go through a remediation process to kill the microbial impurities. These remediated samples may still fail a PCR-based microbial test due to the presence of the DNA. Another issue with the high selectivity of this method is that other species of potentially harmful yeast and mold would not even be detected. PCR is a technique that requires skill and training to perform and this, in turn, adds to the high overall cost of the test.

Both TYMC and PCR have associated advantages and disadvantages and it is important to take into account the cost, speed, selectivity, and sensitivity of each method. The differences between the two methodologies would lead to a large disparity in testing standards amongst labs in different states. In a nascent industry, it is prudent for state regulators to reference specific testing methodologies so that an industry standard can be established.

This is a great outline of the differences between plating and DNA-based methods. Well done.

I’d like to add that while TYM plates are great at giving an indication of overall cleanliness, they do a poor job of excluding off-target organisms (i.e. bacteria). This can artificially inflate CFU counts, and fail samples inappropriately.

Medicinal Genomics has published two peer-reviewed papers that show this (http://f1000research.com/articles/4-1422/v2 https://f1000research.com/articles/5-2471/v1). One potential issue with this exclusivity problem is it could discourage the use of beneficial microbes and lead to more chemical pesticides, such as Myclobutanil.

If you are interested in discussing these issues in more detail, I’d be happy to connect you with our CSO.

Another drawback of TYMC is that it penalizes outdoor growers. Natural colonization by endophytic and epiphytic microorganisms will occur at much higher densities in outdoor plant material than indoor. Most of these are beneficial to the plant and very few are of health concern (Mainly aflatoxin producing and pathogenic species of Aspergillus).

I would strongly urge towards PCR and species identification for states requiring testing. In Oregon I believe they went from TYMC to moisture testing (i guess with the assumption properly dried Cannabis will not allow microbe growth).

I have not seen a lot of data for an unusual number of positives for outdoor grows utilizing TYMC. If anything, I would think PCR would be more sensitive. Beneficial bacteria should not show up on either one if performed correctly. I am concerned about other molds not mentioned in regs and also how testing will be conducted on remediated material. Oregon still requires microbial testing apart from moisture testing but it’s not very specific at all.

Excellent article.

Here are a few more drawbacks to using TYM plates. According to the below DNA sequencing studies, 60% of the DNA on these plates is actually bacterial thus creating a very high false positive rate. High FP on TYMC induce more fungicide use like Myclobutanil. This compound is the cause of the most failures in cannabis labs. Once properly regulated, if we continue to issue false TYM fails, we may see growers use other ‘unlisted’ fungicides as they attempt to rescue crops. Better to have more specific tests that informative and actionable for growers.

The other issue is that TYMC tests cant readily discern a single CFU from 1000 CFU due to Aspergillus tendency to make heterogeneous macro-colonies. This creates sampling bias described here- https://www.medicinalgenomics.com/cultures-failure-to-detect-aspergillus/

Your best defense against Aspergillus is Tricoderma which grows readily on TYM plates thus these plates prohibit growers from using organic beneficial microbes. Likewise dangerous microbes like Clostridium are anaerobes and dont culture without alternative medias. Botrytis and Powedery mildew, also don’t culture. 99% of microbes don’t culture. Most of them can be surveyed with ITS PCR and to the extent they can be cultured, ITS PCR can also discern viability with Pre and Post enrichment PCR.

https://f1000research.com/articles/4-1422/v2

https://f1000research.com/articles/5-2471/v1

While powdery mildews as are obligate biotrophs and cannot be cultured, B. cinerea is necrotrophic and can be cultured easily. Neither of these are a known health concern to humans beyond irritation from spore inhalation or allergies.

These are all great points- plate counts by nature are not very specific, but I do think its better to collect some data on what organisms specifically pose problems in the supply chain before naming specific species. It is dangerous to exclude or include species till we have more data. And honestly, different states may see different microbes be problematic since humidity, soil conditions, nutrients would vary so much.

I fully agree there should be a backstop test/biobank for cases of novel strain outbreaks. This is the one fear I have of species specific only regulations. They might miss the next O157 outbreak. I’m less certain there should be pass fail threshold for such a backstop as we have no idea what any of those organisms are. If we had retains of DNA for all samples tested in the last 30 days, the community could nail down any outbreak quite quickly. What we found so fascinating was the discordance between microbiomes harvested right off of the plant and the microbiomes after culture. Completely different. The new culture environments carbon source completely shifts the microbiome such that you are not actually measuring whats on the plant or exposed to the consumer, but what selectively grew in ones altered lab environment. It’s a Heisenburg uncertainty generator which I think is unfair to place as a pass-fail criteria for growers striving for more microbiome conscious agricultural techniques. But you are wise to realize encumbant technologies have a much stronger grip than most people think.

Mold due to moisture can be avoided if moisture can be pulled from air and plant. NOT all desiccants are created equal and all do not have the same power. A Silica Gel bead in a bag is basically dried sand baked in and oven…….it does not seek out moisture very well, and the moisture it does grab, only sticks to the surface of the bead. Alternative technology includes synthetic desiccants which seek out hydrogen and oxygen atoms individually and pull in and hold moisture………….big difference. for more information, visit the desiccant section at http://www.steelcamel.com

The 24 to 48-hour incubation period for TYMC testing is definitely a challenge when it comes to the speed of results, but it’s good to know that it can detect a wide variety of yeast and mold species. I think it’s especially important to note how TYMC can identify not just harmful species like Aspergillus and Cryptococcus, but also the non-pathogenic molds that could still cause allergic reactions. It’s a reminder of how critical it is for cannabis products to be thoroughly tested to ensure consumer safety.